Behavioral Economics assessments in times of pandemic

The world has changed, and it has most likely changed forever. Our routines and lifestyles have been abruptly altered by the emergence of the COVID-19, a virus which has rapidly expanded and forced most of the population to be homebound. We are facing an unprecedented health crisis, originated by a rare and unpreceded pandemic, which affects nearly all corners of the world. Faced with this reality, we find ourselves navigating in the fog of uncertainty, both personally and professionally, which may modify our behavior and decisions, and directly influence our social, physical, and digital environment. In a crisis like this one, in which the virus spreads by personal contact and individual prevention strategies are crucial to control the pandemic, people´s behavior must be at the heart of the debate.

Given our experience in the study of human behavior, at Kodo People we know the importance of associating the present circumstances to people´s behavior to be able to predict patterns and design effective interventions. Accordingly, key questions to be answered are: Which is the behavioral profile of those most worried about the COVID-19 crisis? Is being directly affected by the virus associated with changes in behavior? Answering these questions has important implications for both public policy design and organizational management. As a pioneering company in the application of Behavioral Economics techniques to Human Resources management (see Samson, 2019), we wanted to put our expertise in evaluating behavioral profiles at the service of the study of the COVID-19 crisis.

HIGHLIGHTS

1) The most concerned individuals are those who are the most trustworthy (with highest positive reciprocity) and the least selfish.

2) The perception of being directly affected by COVID-19 may lead us to make more impatient decisions.

OUR CONTRIBUTION

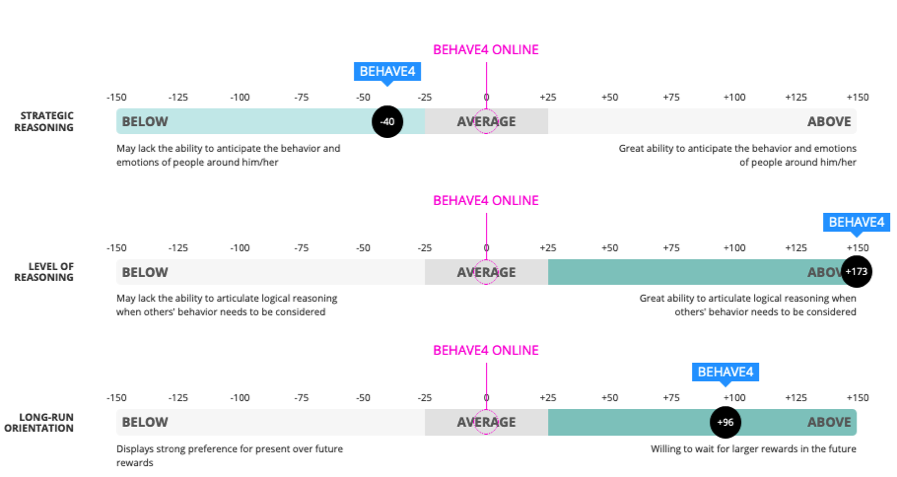

At Kodo People we take full advantage of our technology to shed light on the effects of the current situation on the preferences and behaviors most commonly assessed by companies. For this purpose, we conducted an online study where participants were given a report (for free) about their behavior in so-called “economic games”. Such a report is similar to those received by companies when current or prospective employees are evaluated using our methodology based on Behavioral Economics. Some of the measures disclosed in each participant´s report refer, for instance, to her levels of risk and loss aversion, long-run orientation, compassion, or trust and trustworthiness. Thus, the Kodo People team offers their services selflessly to play our part by presenting an initiative which is at the same time playful for the participants and informative from the personal and scientific points of view.

Our contribution is based on the use of our individual measures of preferences and behaviors, obtained through economic games, in order to predict several variables of interest as we do in one of our most demanded services in Kodo People. In the case of companies, the variables that are typically predicted are the KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) of job performance; that is, the goal is to uncover the behavioral profile of the most productive employees. In this case, we will focus on two main variables related to the study goals: people’s concern about the COVID-19 crisis and their perception about the possibility of having been infected by the virus.

In short, thanks to the data collected in our pilot study, based on economic games, we have been able to achieve very interesting findings by merging the COVID-19 crisis and people’s behavioral styles. From Kodo People, we would like to share this experience and knowledge with all of you.

ECONOMIC GAMES

The methodology based on Behavioral Economics offers fundamental advantages to measure preferences and behaviors compared to traditional techniques (Espín et al., 2017; Samson, 2019). On the one hand, measurements are based on standard economic games which, unlike self-reported questionnaires, allow us to observe specific behaviors instead of attitudes or intentions. The economic games involve real decision-making, with real economic consequences, which provides significant advantages with regard to the use of other assessment techniques. The participants in an economic game, or “players”, are asked to make decisions which involve the use of real money (methodological reward) and are designed so that the players’ choices allow to discriminate between different preferences (which is known as “incentive compatible”; see for example Smith, 1976).

On the other hand, such decisions considerably reduce the effect of social desirability bias, common to the vast majority of traditional assessment methods. Our economic games are not context-dependent, so the decisions involved are set up based on abstract situations to prevent that the participant associates them with concrete life experiences. For this reason, participants do not clearly recognize the variable being assessed and, thus, are not able to choose the most socially valued option or to adapt to a particular goal. The benefits of the methodology applied enable us to evaluate the behavioral preferences of individuals and predict future behaviors in an objective, reliable, and practical manner.

THE ONLINE STUDY

The study has been made possible by our online assessment platform Behave4 Diagnosis. To join the numerous social initiatives which encourage staying positive during isolation, we benefited from Behave4 Diagnosis versatility and offered any anonymous user a free assessment of some of the variables most commonly assessed in companies´ recruitment processes. This study´s goal is twofold: (i) uncovering potential implications of the current situation for the economic behavior, and (ii) testing the performance of Behave4 Diagnosis in a context of massive (and uncontrolled) participation, rather than in the controlled environment of companies.

The advantage of using economic games is that they allow us to measure real instead of self-reported behavioral preferences. For instance, the participant in an economic game that measures long-run orientation has to decide whether she prefers an amount of money at an early date (in our case, 45€ in one month) or a higher amount at a later date (from 48€ to 72€ in two months). The individuals who are willing to wait an extra month for a small amount of money (e.g., 48€) are more oriented to the long run than those who require a higher amount to wait (e.g., 72€).

The study included several economic games like the above, and the data was collected between Friday 2nd April and Monday 6th April, 2020. After the economic games, all participants completed a demographic questionnaire which also included questions related to the COVID-19. The games and the questionnaire were available both in Spanish and English, and completing them required less than 10-15 minutes in total.

As mentioned above, one of the goals of this study is to serve as a pilot to test the performance of our methodology when behavioral assessments with massive and “uncontrolled” calls are carried out. The publication of the study was spread through our main social media accounts, Twitter and LinkedIn, as well as through several forums and private business channels. Any interested person was offered the opportunity of receiving a free and automatic report about her behavior in our platform. The participation and the decisions were completely anonymous, as it is standard in the Behavioral Economics methodology. In addition, we announced that upon finishing, participants would enter a draw to get paid for real according to one of their decisions in the economic games. One out of every 100 participants were randomly selected, by a lottery-like game at the end of her participation, to receive the real amount of money associated with one of her decisions in the games, also randomly selected. The decisions involved considerable amounts since, if selected, a person could win between 0€ and 500€. This is key to our methodology: the assessed person must know that the decisions made in the games have real economic consequences, sometimes even for others’ pockets. In fact, several fortunate individuals have already received their reward. The average earnings were 32€ and the payments were made using PayPal, to ensure they were safe, anonymous, and quick.

THE BEHAVIORAL VARIABLES ASSESSED

We will show the results regarding only some of the 14 behavioral preferences that were assessed and incorporated in the report. In particular, we will mention here only those measures which result in statistically significant relationships with the COVID-19-associated variables.

On the one hand, we included variables related to the decision-making style. An example is a long-run orientation, mentioned above, which distinguishes between people who weigh more the long run in their decisions (“patient” individuals) and those who show a stronger preference for the short run (“impatient” individuals).

On the other hand, we also included measures about distributional social preferences. These measures are typically obtained by using games of resource allocation between several individuals (Charness & Rabin, 2002). The first example of these is social efficiency. It refers to the preference for maximizing the total welfare of a group of individuals, regardless of how it is distributed between group members. Another example is egalitarianism, which refers to the preference for minimizing welfare differences between the members of the group. A motivation commonly in conflict with either of these social preferences is, obviously, selfishness, defined as the preference for maximizing one’s own benefit, disregarding others´ welfare. Our assessment also contained a measurement of selfishness.

Finally, we included measures of social behavior, such as trust and trustworthiness. These variables are typically elicited using trust games (Berg et al., 1995). These games simulate a situation in which one person, player 1, decides whether to send an amount of money to player 2 (i.e., to trust her) and player 2 decides whether to return the favor (to be trustworthy) or, instead, keep all the money. Player 1´s decision measures the level of trust in others, whereas player 2´s decision measures the level of trustworthiness or positive reciprocity.

In Appendix A, we display the definitions of all the measures gathered. In Appendix B, we include an example (fictitious) of the report provided at the end of the participation.

RESULTS OF THE PILOT STUDY

In order to offer relatively conservative results considering the heterogeneity of our participants, we take as statistically significant only those results yielding more than 90% confidence level (linear regression model) in two different samples: (i) the total sample of participants (only using the first participation for those IP addresses featuring more than once: 408 participants) and (ii) a restricted sample of participants who live in Spain, and have unique IP address and a reliable participation (i.e., consistent decisions in more than 50% of the cases), which resulted in a total of 258 participants.

The final sample with unique IP consists of a total of 408 participants (33% women) with an average age of 35 years old (Standard Deviation = 13 years), and brings together people from 26 countries, including the United States, United Kingdom, Italy, and Iran. The majority of participants, however, live in Spain (79%).

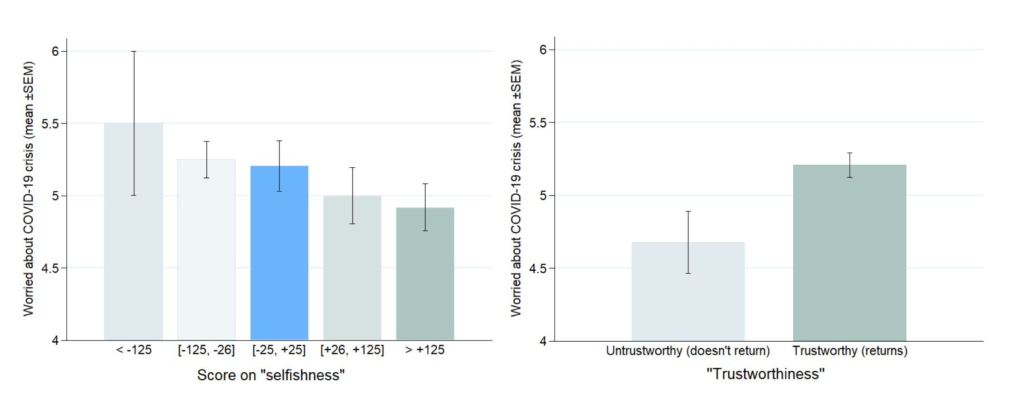

We proceed now to the main goal of this study, which was to investigate the relationship between COVID-19-associated factors and behavioral preferences. First, we focused on the participants´ concern about the COVID-19 crisis, measured by answers to the question “How worried are you about the current COVID-19 crisis?”. The answers ranged from 1 to 7, from “not at all” to “very much”. We observe here that participants displaying high scores on our behavioral measure of selfishness are significantly less worried about the COVID-19 crisis than those with low selfishness scores (see Figure 1, left panel). Similarly, individuals classified as trustworthy in our games (i.e., who returned the favor to those who trusted them) are significantly more worried about the current COVID-19 crisis than untrustworthy individuals (see Figure 1, right panel).

These results point in the same direction as other recent studies about the COVID-19. For instance, Jordan et al. (2020), in an online study conducted in the United States, found that messages focusing on the avoidance of infecting others (prosocial messages: “wash your hands to avoid spreading coronavirus”) are more effective for promoting individual COVID-19 prevention strategies than messages focusing on the avoidance of infecting ourselves (self-interest messages: “wash your hands to avoid getting coronavirus”). According to our preliminary results, being worried about the COVID-19 crisis, as in the case of implementing prevention strategies, seems to be related to viewing life through the other-regarding rather than self-centered lens. Similarly, the fact that the most trustworthy participants (i.e., with more positive reciprocity) are strongly concerned may indicate that people worry more about the current situation the more they perceive others to be worried as well, as if being concerned about the situation followed some sort of social norm.

Apart from their concerns, we also studied the participants´ perception about the possibility of being or having been infected by the virus through the question “Are you or have you been infected by the COVID-19?”. The possible answers were “Yes, I have been tested positive”, “Probably yes, but not tested”, “Probably no, but not tested”, “Definitely no, I have been tested negative”. None of the participants reported having been tested positive. Therefore, we focused on the other three possible answers. For this variable, we found an interesting result related to intertemporal preferences, that is, our long-run orientation behavioral measure. Individuals who answered “Probably yes, but not tested”, show significantly more impatient preferences (i.e., lower long-run orientation) than those who were sure of not having been infected (see Figure 2). This result follows the logic in the scientific literature, which indicates that our attitude towards time is affected by relevant events that impact our mortality, health or stability (e.g., Frankenhuis et al., 2016, Kuralbayeva et al., 2019). According to our results, the perception of being directly affected by COVID-19 may lead us to make more impatient decisions, in other words, to weigh more the short than the long run.

In addition to these findings related to the COVID-19, we obtained other results that replicate those from the scientific literature and, therefore, reinforce our confidence in the informative validity of the data collected. In this respect, we observed that more long-run oriented individuals are less competitive/envious and more socially efficient (Crockett et al., 2010; Espín et al., 2015, 2019). Furthermore, we also found that (i) more selfish individuals trust others less and are less trustworthy, and (ii) more altruistic individuals trust others more, whereas more egalitarian individuals are more trustworthy (Ashraf et al., 2006; Espín et al., 2016).

CONCLUSIONS

Conducting this pilot study has allowed us to achieve several goals. First, we have proven the proper functioning of our platform, Behave4 Diagnosis, in collecting reliable large-scale data remotely. Moreover, we have been able to replicate some of the most consistent results in Behavioral Economics literature.

Based on a reliable dataset, therefore, we have unveiled interesting aspects of the relationship between the COVID-19 crisis and individuals´ behavioral preferences, which are also aligned with the results from recent scientific studies. Our results indicate that the most concerned individuals are those who are the most trustworthy (with highest positive reciprocity) and the least selfish, which suggests that those who worry the most, do not do so in a selfish but a prosocial manner, as if following a generalized-reciprocity social norm. Another important implication of this result is that by analyzing individuals´ behavioral profiles, we might be able to predict who would worry the most in a dramatic situation like the current one (with all its implications), which would allow us to anticipate and implement specific interventions for each type of person.

We also found an indication that perceiving a greater risk for one’s own health, i.e., a higher probability of being infected, is associated with a stronger short-run orientation. The fact that the COVID-19 affects our temporary preferences in such a way, even though this is an apparently adaptive response, may have consequences in a number of behaviors, and these might not be positive. Not in vain, the list of situations in which there exists a trade-off between short- and long-run cost/benefits is endless (within organizations, for instance, standing out to get a promotion, cooperating with team members, increasing effort to get an annual bonus or reprimanding others´ misbehavior). Understanding these behavioral changes is crucial to predict and successfully manage them.

To sum up, our results suggest that (i) individuals with certain behavioral profiles are more prone to be concerned about dramatic situations such as the present one, and (ii) the current environment of uncertainty and risk for our health may have an impact on our behavioral preferences, in particular, on our long-run orientation.

REFERENCES

Ashraf, N., Bohnet, I., & Piankov, N. (2006). Decomposing trust and trustworthiness. Experimental Economics, 9(3), 193-208. doi: 10.1007/s10683-006-9122-4

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., & McCabe, K. (1995). Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games and Economic Behavior, 10(1), 122-142. doi: 10.1006/game.1995.1027

Charness, G., & Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), 817-869. doi:10.1162/003355302760193904

Crockett, M. J., Clark, L., Lieberman, M. D., Tabibnia, G., & Robbins, T. W. (2010). Impulsive choice and altruistic punishment are correlated and increase in tandem with serotonin depletion. Emotion, 10(6), 855-862. doi:10.1037/a0019861

Espín, A. M., Correa, M., & Ruiz-Villaverde, A. (2019). Patience predicts cooperative synergy: The roles of ingroup bias and reciprocity. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 83, 101465.doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2019.101465

Espín, A. M., Exadaktylos, F., Herrmann, B., & Brañas-Garza, P. (2015). Short-and long-run goals in ultimatum bargaining: impatience predicts spite-based behavior. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 9, 214.doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00214

Espín, A. M., Exadaktylos, F., & Neyse, L. (2016). Heterogeneous motives in the trust game: a tale of two roles. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 728. Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00728

Espín, A. M., Reyes-Pereira, F., & Ciria, L. F. (2017). Organizations should know their people: A behavioral economics approach. Journal of Behavioral Economics for Policy, 1(S), 41-48.

Frankenhuis, W. E., Panchanathan, K., & Nettle, D. (2016). Cognition in harsh and unpredictable environments. Current Opinion in Psychology, 7, 76-80. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.08.011

Jordan, J., Yoeli, E., & Rand, D. G. (2020). Don’t get it or don’t spread it? Comparing self-interested versus prosocially framed COVID-19 prevention messaging. doi:10.31234/osf.io/yuq7x

Kuralbayeva, K., Molnar, K., Rondinelli, C., & Wong, P. Y. (2019). Identifying Preference Shocks: Earthquakes, Impatience and Household Savings. Mimeo. https://editorialexpress.com/cgibin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=ESWM2019&paper_id=622 (16/04/2020)

Samson, A. (Ed.) (2019). The Behavioral Economics Guide 2019 (with an Introduction by Uri Gneezy). Pp. 50-62. https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/the-be-guide/the-behavioral-economics-guide-2019/ (16/04/2020)

Smith, V. L. (1976). Experimental economics: Induced value theory. The American Economic Review, 66(2), 274-279.

Appendix A:

Definition of the variables included in the study

Strategic Reasoning: Refers to the ability to understand how people think so that the individual can anticipate others’ behavior in order to make contextually-appropriate decisions that maximize welfare. In other words, strategic reasoning measures the ability to know how smart/strategic other people are.

Level of Reasoning: Refers to the ability to solve complex iterative problems using “backward induction”, that is, the process of reasoning backwards in time considering other people’s expected behavior (as is for instance typically done in playing chess).

Long-run Orientation: Refers to the differences in the relative valuation of rewards (monetary or not) at different moments in time. People tend to prefer rewards that are close in time compared to others that are more delayed, even when the latter are larger.

Risk Aversion: Refers to the preference for values with low volatility. Risk averse people tend to prefer outcomes with reduced level of risk instead of more risky ones, even when the latter are associated with higher profitability (economic or non-economic).

Risk Neutrality: Refers to the preference for maximizing the expected return when making decisions under uncertainty, disregarding the risk levels of the different options.

Loss Aversion: Refers to the tendency to value losses more than benefits, which typically leads to avoid risks when eventual losses are possible. Psychologically, the magnitude of the dissatisfaction associated with losing a certain amount, on average, doubles the magnitude of the satisfaction linked to earning the same amount.

Trust: Refers to the tendency to believe that a person or group will act appropriately in a certain situation. Trustful people do not fear being on others’ hands as they expect others to reciprocate their trust.

Trustworthiness: Refers to the tendency to generate trust, acting with a positive and favourable attitude towards the demands and expectations of others. A person is trustworthy when s/he does not take advantage of the trust that others place in him/her. Closely related to positive reciprocity.

Envy: Refers to the aversion to unequal distributions of outcomes when the individual gets less than others (disadvantageous relative position). Envious people suffer when they are worse-off than others, in relative terms.

Compassion: Refers to the aversion to unequal distributions of outcomes when the individual gets more than others (advantageous relative position). Compassionate people suffer when others are worse-off than themselves, in relative terms.

Egalitarianism: Refers to the preference for minimizing welfare-differences among people.

Altruism: Refers to the preference for increasing the welfare of other people.

Social Efficiency: Refers to the preference for increasing total welfare of a group of people, disregarding the within-group welfare distribution and the differences among group members.

Selfishness: Refers to the preference for maximizing one’s own welfare, disregarding others’ welfare.

Appendix B: Individual Report

Join Kodo People and take your hiring process to the next level!